The windows rattled, that one picture hanging on the wall tilted again, our conversation stopped. We did not notice.

Growing up beside a busy Canadian National railway, trains were a part of life. The engineers blew their whistles as they approached the road crossing, and the roar of the diesel engines as they made their slow way up the Niagara escarpment drowned out everything, making conversation on the deck impossible. Our brains are magical and can tune out almost anything. A guest once noted how loud the train that had just passed was and our response was “what train…”. We would continue the conversations where we had left off, my Mom would straighten the picture as she walked by, and our day would go on as if nothing had happened.

We had a healthy respect for the iron monsters that inhabited the tracks beside the house. We knew from a young age that the freight trains would take kilometers to stop, and the trains were sometimes two kilometers long. My Dad would let us stand beside the crossing barriers on the road as they hurtled by and my brothers and I would quickly step back. The noise and wind assaulted our minds and our primal instincts told us to stay far away. Well, far away from the moving trains, but not far away from the tracks.

In the 1880’s trains were the primary method of transportation in Southern Ontario. Roads between towns were mud tracks, sometimes reinforced with logs and optimistically called “corduroy” roads. What I found shocking is how many railway accidents occurred. The Grand Trunk Railway, the dominant railway in Canada in the late 1800’s, regularly saw multiple fatalities and injuries per day. Some were horrific accidents involving an entire train, but others involved individuals falling off trains, and in one case getting snagged by telegraph cables while walking on top of the train. One regular pattern was injuries or death due to someone sleeping on the tracks.

We did not sleep on the tracks, nor did we ever linger. We did on occasion put copper pennies on the track and then crouched far away trying to track the penny as the heavy engine flattened it. Only a few flat pennies were ever recovered, they had a tendency to get flung away at high speeds.

Country living comes with lore and rumors and stories. One extremely foggy morning a few seconds after a train crossed the road I heard a crash and squealing brakes. Fog plays games with sounds and I didn’t think much of it. The story came out later by word of mouth – a truck carrying manure was crossing the tracks from one field to another on an uncontrolled farm crossing, a common occurrence in farming life. The driver stopped his engine, listened carefully and heard nothing in the thick fog, started his truck and began crossing. To his horror a VIA Rail locomotive loomed in his window. The train struck his truck just behind the cab, sending the cab and driver into the field, where he crawled out miraculously unharmed. The train slid to a stop a kilometer away, covered in manure.

There were tunnels under the railway crossing, decades old made of hand hewn stone, ostensibly for water drainage but to us they were paths to buried treasure full of danger and monsters complete with a caved-in ceiling. Rumor has it a younger brother managed to crawl through the smaller one with the collapsed ceiling, making it from one side of the tracks to the other. No treasure was found but bragging rights were established. Don’t tell our mother.

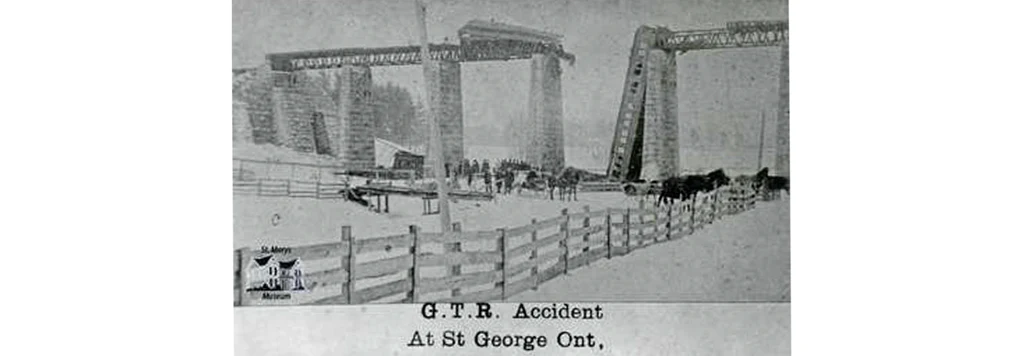

Much to the amusement of my daughters, a young boy lives deep inside every Dad, and the love of trains has not left me. When I moved to St. George, Ontario, I couldn’t help but notice remnants of train tracks everywhere. There is an old tunnel along Highway 5 under the remains of a bridge, built in the same style and era as our childhood tunnels. Two giant concrete abutments stand on either side of Main Street just south of town, slowly being reclaimed by the trees. Town lore, just as wild as country lore, talks about a railway accident involving that bridge, or maybe two accidents, a hundred years ago or more.

Small towns are funny things. There is never a shortage of drama, rumors and arguments about the most trivial things. But when someone is in need, all of that is forgotten and the villagers come together to help in whatever way they can. In early October 2015 a young boy was dying of cancer and was not going to live long enough to see Christmas. His mother asked her family if they could celebrate Christmas early, and the residents of St. George enthusiastically answered “Yes!”. The deathly Halloween displays were quickly replaced with Christmas decorations, and a parade with a hundred floats was organized in a few days. On the evening of October 24, 2015, Evan rode in Santa’s sleigh in the longest parade the town had ever seen as fake snow was blown across his lawn, mingling with the real snow and tears.

Generations earlier the townsfolk came together to aid complete strangers in a much different scene. The descendants of those living in St. George in 1889 still live in the area today. There are still Howell’s on Howell Road, at least one mailbox on Burt Road proudly displays the last name of Burt, and the Roseborough family still farms much of the surrounding land. Brantford’s Daily Expositor wrote in 1889 “The people of St. George did noble, heroic work.” and Hamilton’s Spectator stated “A noble array of heroic women turned out to minister to the dying and wounded.”

On February 27, 1889 just before 6pm, the St. Louis express, a regular passenger train with service from Windsor to Toronto, had a catastrophic wheel failure just before the St. George bridge. The steam engine, tender and smoking car, flying along at 50 mph (80 km/h), derailed but made it across the bridge bumping across the ties, tearing apart the bridge deck behind them. The passenger car fell through the hole and by some accounts flipped end over end before landing right side up in the valley some 60 feet (18 meters) below. The dining car tipped into the valley, landing on one end and resting vertically up against one of the bridge piers. The last car remained on the bridge.

Town lore says that the Grand Trunk Railway was laid a mile south of town, because the surveyor planning the route was overcharged for a book of matches in the village, and out of spite moved the track south instead of through the village. Whether true or not, the bridge was close enough to the village that the residents would have been accustomed to the sounds of the passing St. Louis Express just before dinner and had known immediately that something went badly wrong. They rushed out with every manner of conveyance they had and did what they could to help the dying and wounded. The dining car caught fire, with early diners and staff pinned under chairs and tables and the burning cook stove. Uninjured passengers and villagers put out the fire without any fire fighting equipment and began the rescue. At least two wounded were recovered from where they had fallen off the train into the snow.

The Expositor and Spectator newspapers described how the villagers turned the Mechanics Institute (an early library) into a makeshift morgue, and the thirty badly wounded were spread between Dr. Kitchen’s house, Beemer’s Hotel, and the Commercial Hotel. Dr. Kitchen, the village doctor, must have been overwhelmed with the horrific scene, but no mention is made of it. Later that evening special trains from Hamilton and Woodstock arrived on the scene with more doctors to aid the wounded, and workmen to begin the cleanup. The same trains took the wounded and dead back to their home towns. In the end eleven people died and more than thirty were badly wounded.

The 1880’s were a dangerous time for rail travel. If a passenger train was involved in an accident the results were frequently tragic and received heavy newspaper coverage. Freight trains regularly had accidents as well with fatal results, but received little or no press. One of the wounded recovered in the snow in St. George was Henry Angles, who died the next day. The Daily Expositor published this paragraph March 2, 1889 that caught my attention:

Death of Fireman Angles, the Eleventh Victim – The Latest Particulars

LONDON, Ont., March 1 – Fireman Henry Angles, who was injured in the late accident to the St. Louis express at St. George, died at his home here at 1.30 this morning. Angles has been in two serious accidents before and escaped. He was firing for Engineer Cox when their engine struck an open bridge at Merritton. He jumped and was saved while Cox was killed. When the Port Stanley excursion train dashed into an oil train at St. Thomas in July, 1887, and many were burnt and killed, Angles was firing for Engineer Donnelly. Angles escaped by jumping but his mate was killed. In Wednesday’s disaster the engineer stuck to his post and escaped injury while Angles again jumped, his head striking an abutment of the bridge in his descent.

The St. Thomas disaster was horrific, seventeen people died in that accident. Among the dead were Engineer Harry Donnelly, an engineer with fifty years experience, passengers trapped in the wreckage, and rescuers burned by an oil tank explosion shortly after the accident.

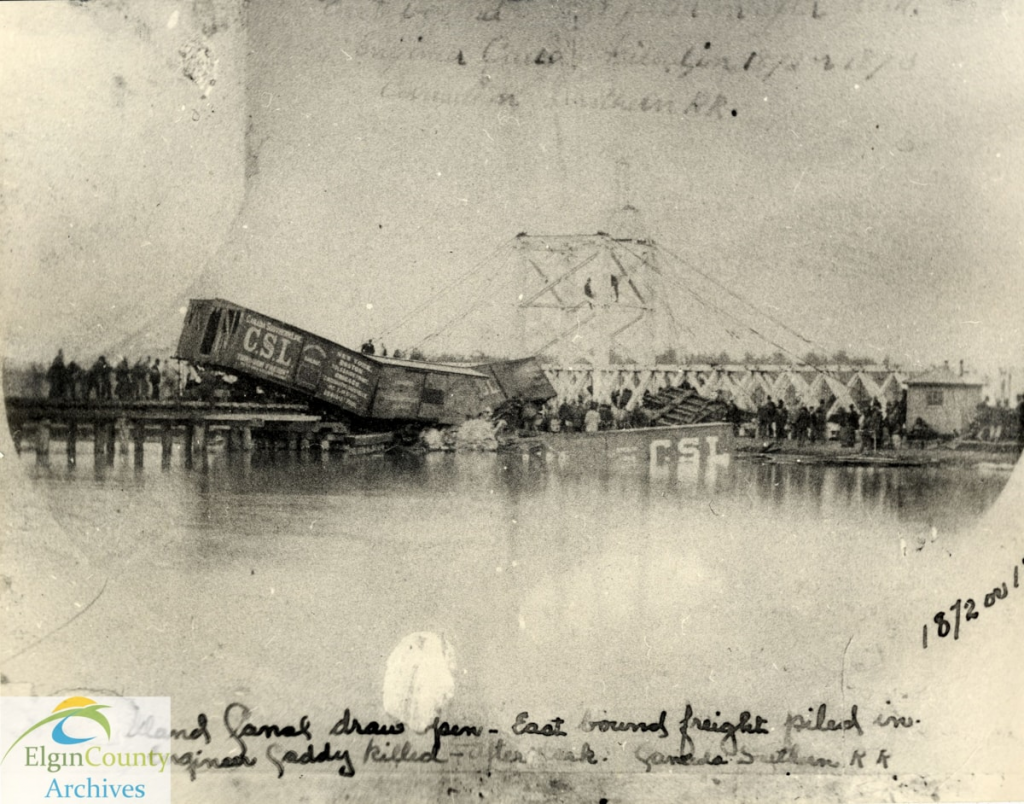

I could not find a record of the first accident Henry Angles was involved in that matched what was written in the Expositor. That wreck likely involved the swing bridge crossing the second Welland Canal just east of Merritton, which today is a council ward of the city of St. Catherines. There were at least three accidents in four years involving the swing bridge that resulted in the train going into the river:

- 1872 – A freight train derailed into the Welland canal, killing Engineer Gaddy. (Source)

- August 18, 1873 – An accident occurred with a passenger train and the bridge, where Engineer Thomas Cox jumped at the last minute and the unnamed fireman stayed with the engine that went over the bridge but survived. No lives were lost.

- April 25 or 26, 1876 – From the Simcoe Reformer published April 27, 1876: A freight train on the Canada Southern Railway on Monday night went into the canal at Welland, the bridge being open. The engineer and a brakeman were killed, the fireman survived reportedly because he was taking lunch in the caboose while the brakemen was covering fireman duties. (Source)

Humans are adept at becoming accustomed to living with dangers or threats that would shock others, and rail travel in the 1880’s was dangerous but with an acceptable risk. Henry Angles was born in New York City, the son of Irish parents who likely immigrated during the Irish Potato Famine with 900,000 other Irish citizens. It’s not clear how he ended up in London, Ontario, where he married Ida Green. Work was a blessing for those who escaped starvation, and holding a well-paying albeit dangerous job on the railway was certainly better than not eating. The tragedy is that Henry survived twice by jumping from a moving train heading to inevitable wrecks, but died doing the same in the third accident.

It is not the steel and noise and speed of trains, exhilarating as that can be, that interests me. Trains bring people together, obviously quite literally by moving people, but it’s the journey and shared experience that builds the connections. Traveling through Europe by train last summer was fascinating, the conversations and memories even in languages I couldn’t understand were so much fun: watching a family with excited young children heading to the beach, a conductor letting a young girl make the announcement for the next station, seeing an incredible Swiss mountain looming through the clouds. Sharing those with complete strangers brought us closer together, even if just for a few minutes.

As horrific as some of the accidents of the past were, the common thread in all of them was the response of the residents of the surrounding towns and villages, and the praise in the newspapers for the random strangers rushing to help the unfortunate. I’m now part of the community who 134 years earlier came to the aid of the passengers of the St. Louis Express. Working together to celebrate Christmas two months early for Evan was a very public highlight of what this village can do.

As horrific as some of the events of today are, there is still a common thread of desire to help each other through it all. The willingness to aid complete strangers is what makes us humans, helping our community is what keeps us from anarchy. Every community pursues this either intentionally or subconsciously, and it’s definitely worth the effort. I hope we never lose the desire to help each other.